I’d like to tell you a story. But before I begin, I’m asking upfront for some leniency because this is a very difficult story to tell. When I’ve tried to tell it before, I’ve felt as if I hadn’t even come close to adequately capturing and describing the incredible series of events that my companions and I experienced this one night about 20 years ago. So many interesting things happened to us in these compressed five or six hours, that it is truly difficult to capture it all. But, let me try!

It started out as a joke, more or less. We were in Paramaribo, the capital city of Suriname, a small country on the northeastern coast of South America. The business meetings with our customer over the previous two days had gone extremely well, and now our work was done. When we arrived back at the Torarica Hotel around five that evening, the four of us, Scott, Kaz, Emory and myself, ended up at the poolside bar for a nice cold Parbo, the local beer. We were due to fly home the next morning. As the equatorial sun fell through the low-hanging clouds towards the horizon, we talked about what we might do to kill time that evening, wishing for something more exciting than just sitting around the hotel bar. “Let’s go turtle watching!”, I joked. Blank stares followed.

I had seen a laminated handbill stapled to a post at the hotel’s fishing pier the day before. The poster advertised that for $70 per person, a guide would take us by boat to a secluded beach that was the site of a new protected nesting ground for sea turtles. After much discussion, and with no other ideas for how to spend the evening, we finally decided that this might be an adventure we shouldn’t pass up. We called the guide.

We’d been in Suriname for three days. All of us had been there before, but none of us had ever really ventured out beyond the secure boundaries of the Torarica Hotel, save for our daily escorted trip from the hotel to the job and back. On past visits, we’d been very careful to stay out of harm’s way. We had heard so many stories about the rampant drug-related crime, the political unrest and the random violence in this troubled country that even going to the little restaurant just a block down the street was a drive, not a walk. There were very few Americans in this place, and we stuck out. As much as I liked the adventure of visiting Suriname, everything about the place was, to me …well, just shady.

Suriname is a cultural melting pot if there ever was one. Its people are descended from Dutch, Indian, Creole, Javanese, Indonesian, Chinese, and Indian ancestors. The country has limited resources. One of its major cash generators back in the eighties and nineties, rain forest timber, was also a resource that most of the civilized world wished it would not disturb. However, the Chinese, who seemingly couldn’t care less about the effects of logging in the rain forest, were there with open purses to buy all the timber that Surinamese would harvest. So, there was a constant stream of huge logging trucks hauling timber from the interior tropical rain forests to the port of Paramaribo every single day. That was a disturbing sight to an American visitor in his mid-thirties who had been hearing about the destruction of the rain forest since fifth grade, and how it could harm the ecological balances of the earth. In Suriname, government leaders, who profited personally in a huge way, chose to look the other way.

With all this in mind, it seemed very encouraging to me that someone, somewhere within the government of Suriname, had finally been convinced by the rest of the world that sea turtles were indeed an endangered species, and one of their most prolific ancient nesting grounds in the world, which just happened to lie on Surinamese beaches, should be protected and managed. I was glad to be supporting this new effort with our American dollars.

A half hour after we spoke on the phone, Gerald, our guide, came to the hotel bar to meet us and arrange the details of the trip. The Matapica beach, where the new government preserve was located, was about two hours away by boat. Gerald said we should plan to stay there for a couple of hours at least. He told us that we were doing this at an ideal time, since the tide, the moon, and weather were all perfect for the trip. He said our chances for seeing some turtles were extremely good. We paid him our money, and he said he’d be back around 6:15 to pick us up at the riverfront pier. We went to our rooms to grab an extra shirt and a towel (what do you pack for a turtle-watching trip?), then met at the pier to wait for Gerald.

As we sat there sipping one last Parbo for courage, we looked out at the Suriname river. It seemed as large as the Mississippi, flowing swiftly northward to its mouth at the Atlantic Ocean. We imagined what Gerald’s boat might look like, and nervously tried to picture what this night might bring. After a while, Scott eventually confessed that he was hesitant to join us on the trip. He withstood our cajoling and ridicule, and finally declared he was just not going. We joked that at least he would be here to notify our next of kin back in the states if the three of us didn’t make it back. Someone – I’m not sure who – sang that line from the Gilligan’s Island theme song…”a three hour tour”… the one that, for anyone our age, immediately conjures up images of a shipwreck and being stranded on a deserted island for life. The tune was now permanently looping in my brain.

Eventually we saw Gerald’s pango boat coming towards the pier. His assistant, Titu, seemed comfortable maneuvering the long vessel up to the end of the pier. The wooden boat was old, but appeared to be sturdy. It sported a fairly new paint job both inside and out – a light pink color, trimmed with blue. It was about twenty feet long and only about five feet wide at its widest point in the middle. The 25-horsepower motor mounted on the stern was at least fifteen years old in my estimation. It puttered rhythmically, with a few syncopated coughs and pops thrown in for emphasis as the boat snuggled up to the pier. The sounds emanating from it reminded me of the music from one of those one-man bands we used to see. I wondered to myself if that little motor would have enough power, and remaining life, to carry all five of us out to our destination and back. I also wondered where the fuel tank was. As we looked at that very small boat, and that very big river, we each secretly wondered if maybe Scott was the smart one of the group.

I guessed Gerald’s age to be about 30. He wore some all-weather pants, worn-out tennis shoes, a blue cotton t-shirt, a yellow windbreaker and a gimmee cap. Once the boat was tied up to the pier, Emory, Kaz and I stepped aboard and took our seats as directed towards the front. I felt vastly unprepared, since the only thing each of us carried with us was a hotel towel and an extra shirt. Gerald assured us that we needed nothing else. The motor stuttered briefly, but returned to a steady rhythm after Titu tinkered with it for a bit.

All aboard, we said our goodbyes to Scott, who stood on the pier above us, arms crossed on the top railing. He was shaking his head in his own disbelief that the three of us were really doing this. I’m sure we looked like first graders boarding the school bus on the very first day of school, with nervous laughter and white-knuckled grips on the edge of the boat.

It was nearly dusk. No one dared to say anything, but all of us noticed the storm clouds that were forming all around us. Sensing our nervousness, Gerald tried his best to put us at ease. As we pulled away from the pier and began our trip down the river, he told us stories about the region, and about himself. We learned that he had spent a good portion of his twenties exploring the northern coastline of Suriname and Guyana on foot. Helping to set the scene for our adventure, he told us stories of the Indians and animals he had encountered in the thick coastal jungles. Gerald had only recently started his little guide business, capitalizing on the recent creation of the turtle preserve and the increased flow of eco-tourist that were now coming to Suriname.

We had traveled only about a half-hour down the river when Titu suddenly steered the boat to the left, towards the riverbank. We knew we couldn’t be at our destination yet, but we had no idea where we were, or why we were stopping. Titu eased the boat alongside a small pier, near what appeared to be a small fishing village. Barefoot children ran out to greet us. There were fishing nets hanging from the trees around the pier. Gerald tied us off, jumped onto the pier and walked swiftly into the village. In just a few minutes he was back, carrying six or seven individually wrapped packages sealed tightly in several layers of Saran wrap. Once he was back on the boat, he carefully placed the packages into a small storage compartment in the middle of the boat under his seat. Emory and I glanced at each other with raised eyebrows. Gerald never said a word to us about where we were, why we had stopped, or what was in the packages he’d collected there. The storm clouds grew taller and more ominous, and dusk was quickly fading into night as Titu started the motor and pointed us back out into the middle of the wide river.

As we reached the mouth of the Suriname river and turned east along the Atlantic coastline, the sun was just below the horizon and its last colorful rays were bouncing off the thunderheads to the west of us, forming a spectacular array of oranges, reds, pinks and grays. It was a sunset like I had never seen before. To our left, out in the water, we passed a series of strange structures that consisted of poles and nets, formed in an almost-closed C-shape facing the shore. Gerald explained that these were fish traps. Once the tide began to recede, the nets would collect hundreds of fish that had been brought in by the tide. The fish would naturally try and swim in the direction of the receding tide, and would be caught in the tight C shaped netting. The Indians would collect them in the morning. To our right was the shoreline. It was close to high-tide, and the beaches were only about 30 feet wide, leading to an intermittent series of nearly vertical dune walls that were about 6 feet tall. Just behind the elevated dunes was an extremely thick (and extremely dark) tropical jungle.

The sun disappeared below the horizon and almost instantly we were in total darkness, save for a small light on the bow of the boat. In the darkness, the soothing drone of the motor and the gentle rocking of the boat from the waves as we moved forward made it feel as if we were being transported to another world. After a while, we heard the music of the motor change and the boat began to slow down. As the motor idled and things got quieter, we heard Gerald and Titu talking in their local slang language called Sranan, or “taki-taki”, which is a creole mixture of English, Dutch, and Portuguese. Their voices got louder and more animated, and it soon became obvious that they were arguing about something. From their gestures and pointing, it appeared that we were lost. Gerald explained to us that we were looking for a particular cove that was sometimes difficult to find, especially on dark nights like this. Titu shut off the motor while they argued about our location and where the cove might be.

As this was happening, I happened to notice an unusual light about a quarter mile from us out on the water. It seemed to be shining directly at us, and flashing in a repeating pattern. I instantly thought of the suspicious packages that we had on board. My imagination took over, and I convinced myself that this was not a random stop. The drug smugglers were signaling at Gerald, and surely they were heading our way to complete some shady pre-arranged transaction!

Gerald and Titu finally agreed that the cove was just ahead of us, and Titu sat back down at the stern and cranked the motor. The motor made some noises, but refused to start. As the three of us looked nervously at each other, Titu tried repeatedly to start the motor, but to no avail. I looked again at the signaling light to try and determine if it was coming our way. While Titu pulled out a set of wrenches wrapped in a cloth bundle, Gerald tried his best to reassure us. He was quite sure that the cove, our destination, was just ahead. We were about 30 yards away from the shoreline. Then he said, “I think it’s pretty shallow here. Would you mind walking to shore?”

Before any of us could remind Gerald that we had come to observe the turtles, not swim with them, we heard the motor suddenly come to life again. I felt my pulse slow down a bit, and all of us let out a collective sigh of relief. Once we were underway again, Titu steered the boat ahead but slightly towards the shore, headed towards some unseen point in the darkness. As we got closer to the shore, I could in fact make out a small cove where the beach split and a small rivulet went inland and then made a sharp turn to the left. We puttered slowly into the rivulet, and the boat came to rest on a sandy shoal. Titu shut off the motor. It was totally dark and silent.

We carefully climbed out of the boat, extremely thankful for the chance to put our feet on dry land again. Just in front of us was what looked like a small fishing camp. There were cots that had been recently used, a few Igloo ice chests stacked against a post, and some fishing nets laying on the ground. There had been a fire in the fire pit recently, and some pots and pans were stacked near the pit. It was obvious there was no electricity.

As the three of us looked around and got our land legs again, we became aware that Gerald and Titu were still back at the boat, talking quietly. I could see that Gerald had opened the storage compartment under the center seat and was collecting the Saran-wrapped packages. Without saying a word, arms full, he walked over to an area of the camp that had a sloped tin roof. A chest-high partition formed three walls of what could be described as a small “bedroom” that held a cot and a red Igloo cooler. Gerald opened the cooler, gently placed the packages inside, then closed the lid. He then walked over to us with a big smile on his face (relief?), as if what we had just seen did not really happen. He obviously didn’t want to talk about the packages, and the three of us were too nervous to ask about them. With that little task out of the way, he could now return to being a turtle guide.

This picture doesn’t fully capture the anxiety I was feeling at the moment:

The camp was situated about 10 yards from the beach. Directly behind the structure, on the opposite side, we could only see darkness – the edge of the jungle. Gerald called us together and began to tell us about the turtles and their behavior, and what we could expect to see. Just as I felt myself relax a bit, I noticed some movement at the edge of the woods.

In the total darkness, it was impossible to make out what or who it was until Gerald finally shone his flashlight in the direction of the movement. Two men appeared, their skin as dark as the night. They had obviously just woken up. The guy in front scratched his disheveled hair, rubbed his eyes, and worked at buttoning up his shirt. Both were dressed in dark blue long pants with the belts still unbuckled. One wore a flowered short-sleeved shirt and the other wore a white long-sleeved shirt. In the scattered beams of Gerald’s flashlight, I could barely make out an old, faded patch on one sleeve. One thing that I could definitely see was that they both wore guns on their belts.

We could not understand the taki-taki conversation going on between them, but it seemed as if Gerald knew them. The two men examined us from head to toe, nodding as Gerald spoke. Finally, the two men smiled a little and the conversation was over. Gerald turned to us and said, “Let’s go see turtles!”. Relieved, but still very much in the dark in a lot of ways, we followed Gerald towards the beach.

The four of us walked through the jungle towards the beach with only Gerald’s flashlight to light the way. The trees and brush eventually parted, revealing a beautiful white sandy beach in front of us with the gentle roil of the surf making the slightest churning sound. My adrenaline rushed as Gerald began to describe what we should be looking for. “Have you ever seen the tracks behind a Caterpillar bulldozer?”, he asked. “That’s how we will know that mama has come to shore.” We had walked only another 20 yards or so when we saw our first set of tracks. They looked just as he had described them.

Gerald had told us earlier that the mama turtles were extremely particular about where they make their nest. They may come ashore, investigate the area, and if something is not quite right, they will go back into the ocean. Conditions must be absolutely perfect for her to create a nesting spot.

We followed the enormous tracks, walking slowly and quietly. Eventually, in the darkness, we could make out the shape of the mama turtle. She was about three feet long from head to tail, and the top of her shell was about two feet above the beach sand. We moved towards her slowly, then crouched and just watched while she slowly moved around the beach. Gerald identified her as a green sea turtle. The two most common turtles to nest on these beaches are the greens and the leatherbacks. We stayed far enough away that we wouldn’t interfere with the process. But we could see her outstretched head as she looked around and smelled the air. She would take a few steps in one direction, stop, smell, and then turn in another direction until she had evaluated the entire scene from every angle. We could hear her grunt and snort as she made each deliberate, slow move. Her breathing was loud and heavy, but very slow.

Suddenly, Gerald whispered, “Let’s go ahead to her, I can tell she’s going to leave. It’s just not right for her.” As he said those words, the mama green turned and started making her way directly back to the water. Once we were certain she was leaving, we took the opportunity to get closer. We moved close enough to reach out and touch her as she reached the surf. Thrilled and disappointed at the same time, we watched as she gradually disappeared back into the sea.

We continued walking down the beach, and had only walked about a quarter mile when Gerald suddenly put his hand up. We stopped in our tracks. Gerald’s trained eye could see another set of tracks just ahead. They were even bigger than the last set, and very fresh. “She’s here, and I think it’s a leatherback”, he whispered. “Wait here and let me go see”. We stayed behind, kneeling in the sand as Gerald slowly walked up the beach further and disappeared into the darkness. In just a few minutes, he was back. “We’re lucky!” he said. He explained that the mama leatherback was just ahead, and was climbing up the dune to the elevated area between the beach and the jungle. She was still investigating the area, but the fact that she was up on the dune was a good sign. “Follow me. We’ll move really slow and just watch her from a distance for now.”

Creeping slowly and quietly, we moved diagonally from the beach up to the top of the dune until we could see her. She was huge, twice the size of the green we had seen earlier. My heart raced, and I could not believe that I was actually getting to see this with my own eyes. Mama had found the perfect spot on top of the dune. It was a clearing about the size of three parking spaces. From her tracks, we could see that she had come onto the beach, circled around a bit, and then followed a shallow trail up to a flat area on the top of the dune that was about six feet above the beach. We watched her circle the area slowly. She finally completed her maternal evaluation and came to rest in the middle of the spot, parked perfectly with her head just a few feet from the edge of the dune. From this vantage point, she had her own spectacular view of the immense ocean directly in front of her.

What came next was a strange but natural process that has been repeated, perhaps at this very spot, for eons. But before I describe what we saw there, there’s a few things you need to know about these incredible creatures.

The leatherback turtle is the largest turtle on earth. They can weigh as much as 2,000 pounds. Scientists have traced their evolutionary roots back more than 100 million years. They lived when T-Rex was alive, but they are now considered an endangered species. They live on average about 45 years.

The most incredible thing is how they travel the world’s oceans, guided by mysterious natural forces that we have yet to fully identify. This mama turtle that we were watching most likely began her life here on this same beach. When she leaves the coast of Suriname, she will roam the Atlantic Ocean for a couple of years. Her leatherback sisters have been tracked by satellite leaving this coast of South American and travelling to places as far away as Morocco and Spain, almost 4,000 miles away. Then, whenever nature tells her the time is right, she will return to this very same area to mate and deposit another clutch of eggs. The leatherback males, once they hatch and make their way down the beach to the water, will never come to land again, spending their entire life in the water.

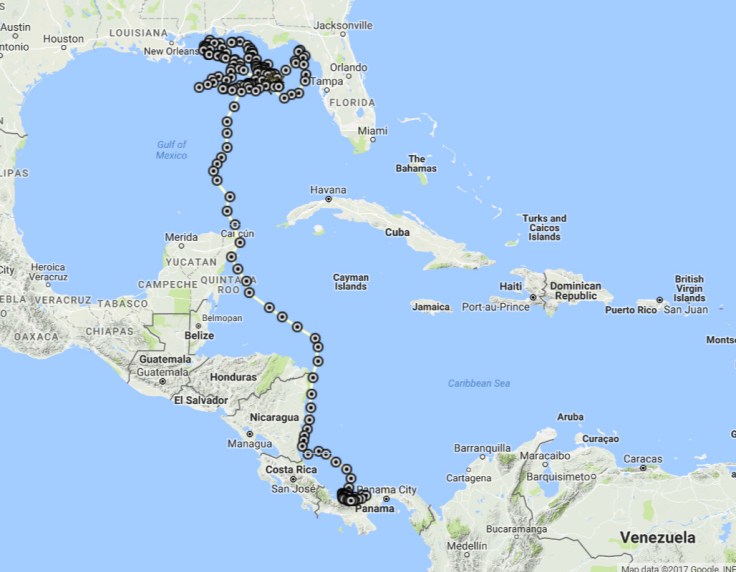

There is one particular female leatherback being tracked by satellite right now. Her name is “Tortuga Tourist”. She was first fitted with a tracking device on June 1, 2016 on the northeastern coast of Panama in Central America. She came back to the beach eight days later and nested. She then spent the month of June cruising off the coast of Panama. On July 1st, she decided to head north. By July 28th, she had reached the coast of Cancun, Mexico. On August 9th, she had arrived in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, where she’s been spending time in the area between Mobile, Alabama and Tampa, Florida. Just yesterday, she was about 100 miles west of Tampa. Since they started tracking her last summer, she has logged 4,001 miles. She’ll continue to cruise the oceans for a few years, feeding on hundreds of pounds of jellyfish each day, until that unexplained call of nature beckons her back to the beaches of Panama to complete the cycle and begin it again.

The mama we watched sat totally still for a while. We could hear her slow and steady breathing. Her calm stillness told Gerald that she was indeed about to start nesting, and he gave us a thumbs up. Once they are convinced that the location is good and the conditions are right, the mama leatherback enters an almost trance-like state. Nothing will bother her once the process begins, short of jaguar or some other predator forcing her off the nest. We eased slowly around behind her and then quietly moved up until we were no more than 10 feet from her.

I could not believe her size. Her body was teardrop-shaped, rounded at the shoulders in front and sweeping in a taper down towards the back. The leatherback doesn’t have a shell like other turtles, but rather a soft, oily-feeling carapace that looks like a thick tarpaulin stretched over wooden ribs. In the front, she had two massive, wing-like flippers that extended out about 4 feet from either side. While these front flippers provide her with propulsion in the water, she uses the smaller rear fins to steer her massive body.

All of a sudden, she came to life and the process began. With a powerful thrust, her massive body suddenly shifted to one side and one of the short rear fins dug into the soft sand under her tail. Sand sprayed out everywhere from behind her, sailing more than 20 feet over our heads and off to the side. A few seconds later there was an identical shift and scoop in the opposite direction. This incredible combination of power and finesse caught me totally off-guard. It continued for about 10 minutes until those massive rear fins had created a deep hole directly below her tail about 18 inches deep and 2 feet in diameter.

At some point, she instinctively knew she had done enough. The hole was just right and she could stop digging. She remained still for a few minutes. Now that she was thoroughly immersed in the process, we silently and slowly crept up to her side. I touched the oily surface of her thick carapace and pondered where all she had been, what she had seen and felt, as she traveled thousands of miles away and thousands of feet underwater. Her eyes were dark and crusted with salty tear deposits, a result of her almost exclusive diet of jellyfish. As I looked in her eyes, I wondered what she was thinking. Was she sentient at all, perched on this high dune and looking out over her massive ocean, her home? Was she capable of extracting the meaning of all of this, or was she just following some ingrained natural process that she had no control over. How strange is it that through some quirk of evolutionary development (or God’s divine plan), this ancient creature has to leave the watery home where she thrives, and come to this dry land, the polar opposite of her world, in order to simply procreate. She and her kind live almost entirely in the infinite space of the watery ocean, and yet this small area of sand is the critical link in the continuation of her species.

Gerald whispered for us to come back to the rear. He pointed his flashlight underneath her tail and we watched as the stream of eggs started dropping into the hole. Gerald reached under and caught one of the eggs as it fell, and then gently passed it to us to examine. It was about the size of a ping-pong ball, perfectly round. It felt soft, flexible, and very fragile.

When the final egg had dropped, mama began the next phase of the process – sealing them in their ground incubator. She first used her large front fins to move massive amounts of sand back towards the hole. After each massive swing of a front fin, the smaller rear fin on that side would then gently move the sand into place. Like a human mother using her hands, she used those smaller fins to gently pat down the sand and compact it, lift by lift. Then the fins on the other side would do the same. Knowing that the power and weight at her disposal could have easily crushed the entire bed of eggs instantly, the gentleness of this action was amazing to me. The hole was eventually filled with sand and compacted fully.

A typical clutch for the leatherback female is about 80 to 100 eggs. One reason why the species has ended up on the endangered list is because turtle eggs have been considered a food delicacy in many cultures over the years, including in Suriname. Predators in the wild like raccoons, dogs, coyotes, sea gulls and crabs consider the eggs a delicacy too, and will dig them up. As the final part of the process, mama did her best to hide the nest and make it look like nothing had happened here. It was fascinating to watch her as she left the nest and moved a few feet away, taking her long front fins and making a giant sweeping arc, blowing sand everywhere. She moved to four or five different random places and repeated this action. By the time she was finished, you truly could no longer tell where the nest was located.

Her work completed, mama turned to go home. She moved slowly down the slope to the beach, wasting no time in getting back to the water. We walked slowly behind her as she moved, one massive forward lurch after another, leaving the bulldozer trail. When she got to the edge of the water, she paused for a few seconds as the surf came up and washed the land off of her, as if it were welcoming her back home. We watched in amazement as she disappeared, back to the deep.

The three of us were speechless as we walked back to the camp. We had just witnessed something amazing that very few people get to see. The skies had cleared while we were watching mama, and now there were more stars in the sky than I had ever seen before. Gerald pointed out the Southern Cross, a constellation that you can’t see in the northern hemisphere. Titu met us at the edge of the fishing camp. There were no signs of the other two men.

We boarded the boat, and Titu started the motor and headed cautiously down the narrow stream, through the cove and out into the ocean. Once we got out into the ocean, Titu gave it full throttle and we headed back to the river and our hotel. It was a silent ride back, all of us contemplating what we had just seen, until we got to the place where the fish traps were. It was there that Emory looked back at the wake being created behind us and pointed. As if we hadn’t seen enough of nature’s wonders that night, the water behind the boat and in the wake beside us was glowing green and blue with phosphorescence. It was an amazing sight. We stuck our hands down into the water and held the light in our hands. I had heard about ocean phosphorescence all my life, but had never actually seen it. It happens when certain small organisms get stimulated by the churning or movement of water and they become luminescent. There is a famous story told by Jim Lovell, the Apollo 13 astronaut, about the time he was a pilot stationed on an aircraft carrier. He had been out on a nighttime patrol mission when all the instruments and the radio on his aircraft went dead. How would he find his aircraft carrier and safely land his plane? Suddenly he saw a long, glowing light in the ocean. It was the phosphorescence in the ocean from the waters being churned up by the ship’s propellers. It was bright enough to guide him in and let him safely land his plane on the carrier. Our view that night looked something like this:

We made it safely back to the hotel pier where Gerald and Titu dropped us off and we said our goodbyes. It was about 3:00 AM and we had only a couple of hours to sleep before the driver would be there to pick us up for the trip to the airport. I got to my room, set the alarm and quickly crashed, physically and mentally exhausted. The words “sensory overload” came to my mind as I laid down and went to sleep.

On the drive out to the airport the next morning, we shared our story with Scott, and rehashed the night’s events with each other. It had been such a beautiful night, and we all felt blessed to have seen the natural wonders we saw. But all three of us also had these burning questions about some of the unexplained events….Was Gerald a real turtle guide? A drug dealer? A budding entrepreneur? What was in the Saran-wrapped packets? It could have been drugs. But it could also have been cigarettes, or perhaps just food that Gerald brought as a friendly token of appreciation to the two men in the jungle. Who were the men in the jungle? Game wardens? Drug couriers? Fishermen? What was the light offshore that seemingly signaled to us as we searched for the cove? And if this was a government preserve, why wasn’t there a more official-looking headquarters than the run-down fishing camp, with electricity? Most importantly, were the eggs still in the nest this morning?

That night will stay with me forever. I will never forget it. The mixture of intrigue, excitement, fear, and of course the natural wonders that we saw made it…a night to remember.

I read this as if i was on the journey with you. I too, want answers to all those unanswered questions. This story was so awesome that I shared it with Lisa at dinner tonight. Our usual 15 minute dinner went on for an hour as I took Lisa on this journey as well. My friend, you have a great talent for making the paper come alive and immersing your audience into the story. Loved it!

LikeLike

What an amazing adventure…I felt like I was viewing the same incredible sights with the details you wrote. I’m impressed that you had the courage to do this, and that you lived to tell the extraordinary tale!

LikeLike

Loved your story and you were very brave to go out at night not knowing what to expect. We have seen turtles lay eggs in Mexico, the place we stay at has a turtle Sanctuary. It is amazing to see them release the babies and how they all head for the water. The sad part is how few actually survive to adulthood. Donna

LikeLike

Our stories never fail to captivate your audience.

Glad y’all didn’t become captives that exciting night.

Tammy

LikeLike

This was great!! I read and reread this! Very intriguing!

LikeLike

Gosh I feel like I just went on that crazy adventure with you. Sure am glad I didn’t know that was going on. I would have been so worried.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike